Leonora Carrington: the surrealist artist who painted freedom

There are artists who whisper in your ear, and then there is Leonora Carrington, who invites you to dive into a world where animal queens, ancient priestesses, and alchemical creatures dance in an eternal ritual of transformation.

In this article, I take you with me to discover the life (and universe) of one of the most fascinating voices of surrealism: free, restless, rebellious, and above all, indomitable.

Leonora Carrington, a life of rebellion, art, and magic

Leonora Carrington was born in England in 1917, but her spirit knew no boundaries.

Her family was wealthy but strict, and she, who loved freedom, rejected the idea of a pre-packaged existence from a young age. She was expelled from several boarding schools, but found refuge in painting and writing.

In the 1930s, she met Max Ernst and moved with him to Paris. Thus began a passionate love affair characterized by creativity, but also by pain. With the arrival of the war, Ernst was arrested and Leonora, alone and distraught, was committed to a mental hospital in Spain. That traumatic experience gave rise to one of her most powerful texts: Down Below, in which she recounts her descent into the underworld of the psyche.

After fleeing to Mexico, she finally found a place to put down roots, even though her roots, like her works, are anything but earthly.

The most important works Leonora Carrington: a bestiary of dreams

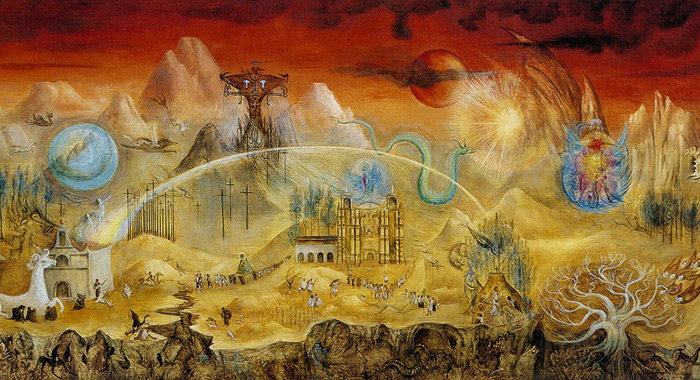

Leonora Carrington’s painting is an esoteric language, a visual alphabet made up of arcane symbols, mythical animals, alchemy, and transformations. Among her most famous works are:

The Lovers (1947): an almost liturgical vision of love, imbued with alchemical symbolism and fairy-tale atmospheres.

The Pomps of the Subsoil (1947): a work that seems to depict an underground magical ceremony, in which each figure is a priestess or a spirit in metamorphosis.

The House Opposite (1945): a domestic interior populated by hybrid figures and mysterious presences, evoking a universe parallel to our own.

The Inn of the Dawn Horse (1937–38): a powerful self-portrait, with Leonora accompanied by her white horse, a symbol of freedom and identity.

Leonora Carrington’s style

It is not enough to say “surrealist.” Leonora Carrington takes the masculine surrealism of Breton and Dalí and turns it upside down.

She is not a muse: she is a sorceress.

She is not an object of desire: she is a priestess of mystery.

Her style combines meticulous, almost Flemish-like strokes with complex compositions, often overloaded with esoteric, mythological, and feminine references. Her figures are never static, but are in constant transformation, as if they were about to be reborn or to free themselves from something.

Leonora Carrington does not paint dreams, but portals. And we, the viewers, are always invited to pass through them.

Some interesting facts about Leonora Carrington that you may not know

Leonora Carrington was also a writer. Her literary work is as brilliant and surreal as her painting.

She believed in magic, for real: alchemy, Kabbalah, Celtic mythology, ancient religions… Carrington did not use them as metaphors: they were real tools of knowledge and transformation.

She loved horses more than anything else: a symbol of freedom and wild intelligence, they often appear in her works. They were also her guiding spirit (or, as she said, her true nature).

In 2015, she was featured on a Mexican banknote: one of the few women (and foreigners!) to appear in this way in the country that welcomed her.

The connection between Leonora Carrington and Peggy Guggenheim

Leonora Carrington stopped in New York in 1941, where Peggy Guggenheim helped her temporarily, welcoming her into her artistic entourage. At that time, Guggenheim was organizing exhibitions and collecting works by surrealist artists who had fled Europe because of World War II.

In particular, Peggy Guggenheim was already supporting Max Ernst, Leonora’s former partner, with whom her relationship had ended. The meeting between the two women took place at a delicate moment in Leonora’s life, as she was still reeling from recent events and undergoing personal and artistic transformation.

Despite this, Leonora was never part of Peggy’s “official circle.” They were both strong, free women, but very different: Peggy was worldly, a wealthy collector, attracted to aesthetics and male talent; Leonora was reserved, unconventional, and animated by an almost mystical spirituality.

Their relationship was therefore brief, but significant as a fragment of the network of connections that allowed many European artists to survive and reinvent themselves in the New World during the dark years of the conflict.

The importance of Leonora Carrington today

In a world that still fears diversity and female freedom, Leonora Carrington is more relevant than ever. She never bowed to what was expected of a woman, an artist, or a human being. She chose to be something else. To be herself, through and through.

She left us an immense legacy: not only works and books, but a constant invitation to free ourselves, transform ourselves, invent ourselves.

As she herself wrote:

“Those who never change shape are lost.”

And you? Are you ready to change shape?

Follow me on:

About me

In this blog, I don't explain the history of art — I tell the stories that art itself tells.