Guillaume Apollinaire: the poet of modernity between art, words and the avant-garde

Poet, writer and art critic, Guillaume Apollinaire was one of the most complex and fascinating figures in early 20th-century European culture. Born in Rome in 1880 and died in Paris in 1918, Apollinaire embodied the restless spirit of a changing era, becoming one of the most lucid and visionary interpreters of artistic modernity.

His real name, Wilhelm Albert Włodzimierz Apollinaris de Wąż-Kostrowicki, already tells a story of cultural crossroads, migration and elusive identities. This condition would profoundly mark his life and his way of looking at the world, always suspended between nostalgia and enthusiasm for the new.

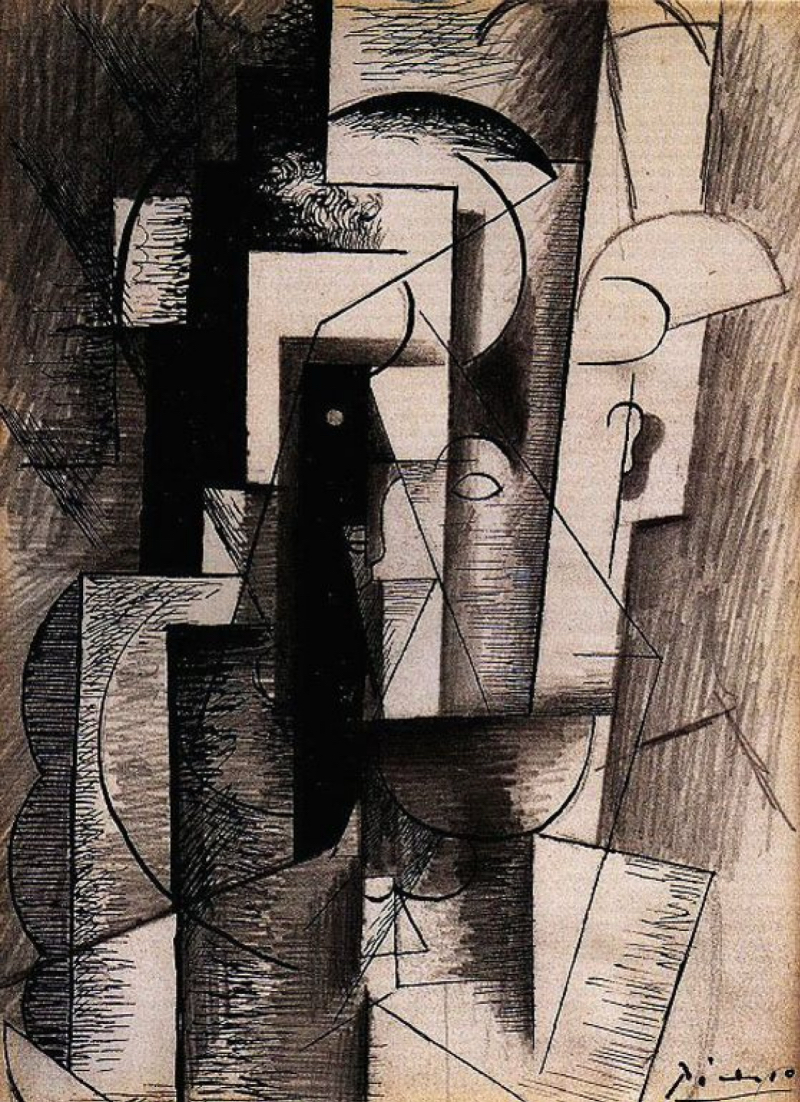

Picasso, Ritratto di Apollinaire (1913)

Guillaume Apollinaire: the poet who taught modernity to speak

Apollinaire lived in Paris at a time when the city was the beating heart of international art.

In the early 20th century, he recognised and supported new directions in art, accompanying the birth of the avant-garde with critical intelligence. He was among the first to understand the revolutionary significance of Cubism and to recognise the potential of Futurism, supporting artists such as Picasso, Derain, Vlaminck and the Italiens de Paris.

His role was never marginal or passive. Writing in newspapers and founding magazines such as Les Soirées de Paris, Apollinaire helped to construct the critical language necessary to interpret an art form that was breaking definitively with the past. Giorgio de Chirico celebrated him as a modern hero, depicting him in military uniform against a black background, symbolising a life torn between two eras. Alberto Savinio, on the other hand, captured his melancholic side, portraying him as a Roman patrician of decadence.

Apollinaire and poetry as a space for experimentation

Even before he was a critic, Apollinaire was a poet.

His writing underwent a profound transformation, reflecting the tensions of the time.

With “Alcools”, published in 1913, he broke with the linearity of poetic narrative, dissolving the temporal sequence and creating surreal, musical and disturbing images. Beneath the apparent stylistic intoxication lie melancholic themes, broken dreams and a subtle loneliness.

His poetry sought a continuous dialogue with the visual arts, at a time in history when speed, simultaneity and dynamism were changing the way reality was perceived. Words alone were no longer enough; they had to become images, rhythms and gestures.

Apollinaire; war, wounds and a new style of writing

In 1914, Apollinaire enlisted as a volunteer, convinced that war was a great spectacle capable of accelerating history. However, his experience at the front profoundly affected his outlook.

Seriously wounded in the head in 1916, he never returned to combat and found refuge and reflection in poetry.

The verses born of that experience are imbued with pity and awareness, close in intensity to those of Ungaretti. The war had wiped out a world and imposed a new, more fragmented and cruel vision of reality. This change found its definitive form in Calligrammes, published shortly before his death.

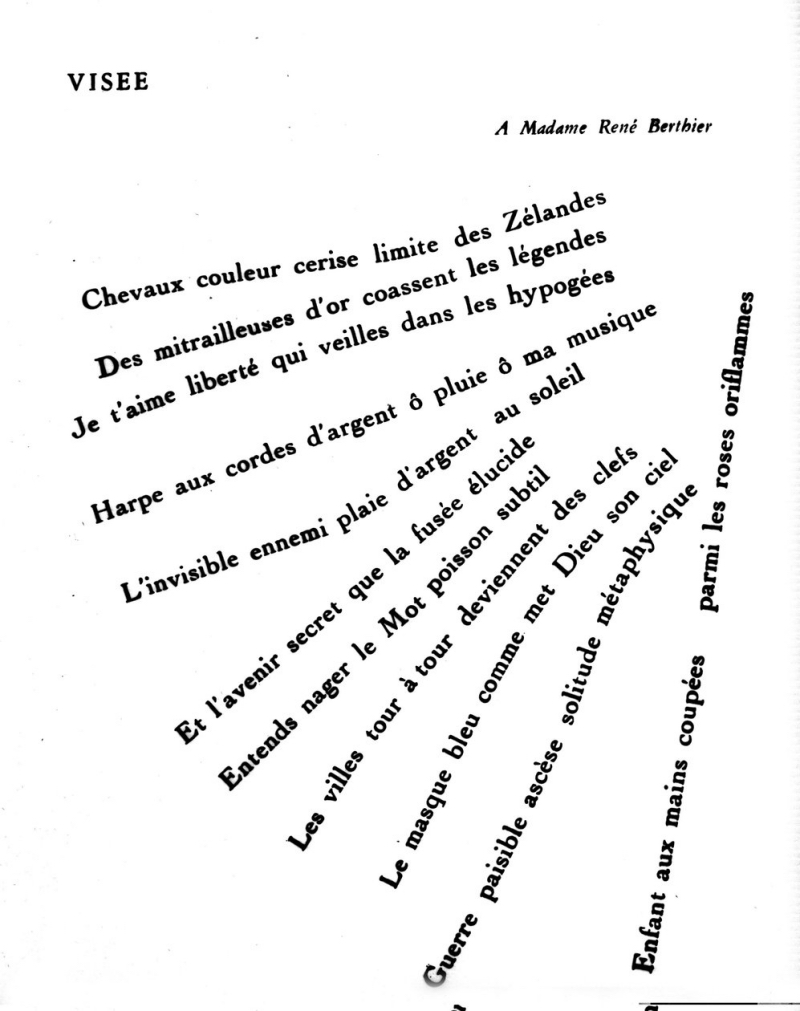

Calligrammes and the invention of visual poetry

With Calligrammes, Apollinaire revolutionised poetic language. He eliminated punctuation, adopted free verse and transformed words into images.

The poems take on visual forms, becoming objects to be looked at as well as read, anticipating fundamental concepts of 20th-century art such as the reproducibility of the work and the dynamism of the sign.

While drawing on ancient traditions, these works represent a poetic response to the era of cinema, speed and movement. In this sense, Apollinaire laid the theoretical foundations for what would become kinetic art, without being able to see its development.

Apollinaire’s surrealist drawings, visions and anticipations

Apollinaire was not just a man of words.

His drawings, only recently rediscovered and published, reveal a surprising visual universe.

Caricatures, fantastic animals, errant knights and deformed bodies populate pencil and watercolour sheets, tracing a dreamlike and grotesque imagery that anticipates Surrealism.

This human bestiary tells the story of a society in crisis, overwhelmed by a distorted modernity that leads to nationalism, violence and a loss of values. Apollinaire’s gaze remains ironic and sympathetic, never detached, deeply in love with humanity in all its fragile complexity.

Calligramma di Guillaume Apollinaire, Calligram Visee

Guillaume Apollinaire died in Paris in 1918, a few days after the end of the Great War, a victim of the Spanish flu. His legacy, however, lives on in poetry, art and in the very way we think about the relationship between words and images.

Apollinaire did not merely describe modernity, he invented it, one verse at a time.

Follow me on:

About me

In this blog, I don't explain the history of art — I tell the stories that art itself tells.