Kinetic Art: history and artists who revolutionised perception

There is a moment in art history when the immobility of painting is called into question and the viewer’s gaze becomes the true protagonist. It is at this moment that Kinetic Art is born, an innovative and fascinating movement that revolutionised the very concept of a work of art.

Kinetic Art developed after the Second World War, just as geometric abstraction began to lose its driving force.

The artists of this new trend were no longer satisfied with composition and emotion. They chose to explore visual perception, to study optical phenomena and light, to translate into painting and sculpture the dynamism that now permeated thought, science and everyday life.

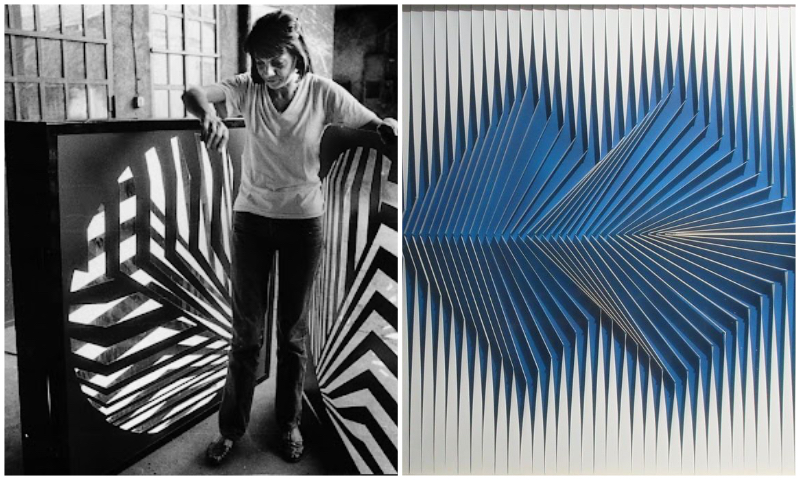

Grazia Varisco e Alberto Biasi arte cinetica

Kinetic Art: when vision becomes movement

The roots of Kinetic Art lie in the historical avant-garde movements of the early 20th century: from Futurism to Constructivism, from Dada to De Stijl, from Bauhaus to Concretism.

As early as 1913 to 1920, artists such as Marcel Duchamp, with his Bicycle Wheel, and Man Ray, with his Rotating Plaques, began experimenting with movement as an artistic element.

In 1920, brothers Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner signed a manifesto in which they explicitly referred to Kinetic Art. Ten years later, László Moholy-Nagy defined the device that powered his Light-Space Modulator as “kinetic”. In Italy, in the 1930s, Bruno Munari created his Macchine Inutili (Useless Machines), visual devices that anticipated the fusion of art and technology.

However, the turning point came with the 1955 exhibition “Le Mouvement”.

1955 marked the official beginning of Kinetic Art as an autonomous artistic movement.

In Paris, the Galerie Denise René hosted the exhibition Le Mouvement, which brought together works by key artists such as Calder, Duchamp, Yaacov Agam, Pol Bury, Victor Vasarely, Jesus Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely, Nicolas Schöffer and Takis.

The public discovered works that moved, vibrated and changed appearance thanks to light or the observer’s gaze. On the one hand, research focused on the effects of optical illusion (Optical Art), and on the other, on the actual mechanics of movement, sometimes natural (as in the case of Calder) or technological (as in Tinguely or Schöffer).

The language is aniconic, far removed from any form of traditional figuration. The aim is to engage the viewer on a perceptual level, transforming the work into an active and immersive experience.

The 1960s: international expansion and the Italian avant-garde

In the 1960s, Kinetic Art experienced extraordinary international expansion.

New variations emerged, such as Lumino-Kinetic Art, based on the use of light, and Op Art, centred on optical perception. Exhibitions multiplied: Kinetische Kunst in Zurich (1960), Moving Movement in Amsterdam (1961), Nove Tendencije in Zagreb (from 1961 to 1973).

In this panorama, Italy played a fundamental role. Not only did it welcome the movement, but it transformed it into a veritable laboratory of experimentation.

Numerous artistic groups emerged, marking an extraordinary phase for visual and perceptual design. Among the best known were:

Gruppo T (Milan, 1959): with Gianni Colombo, Davide Boriani, Gabriele De Vecchi, Giovanni Anceschi and Grazia Varisco

Gruppo N (Padua, 1959): with Alberto Biasi, Ennio Chiggio, Toni Costa, Edoardo Landi and Manfredo Massironi

Gruppo MID (Milan, 1964): with Antonio Barrese, Alfonso Grassi, Gianfranco Laminarca and Alberto Marangoni

Gruppo di ricerca cibernetica (Rimini, 1968)

Group One, Group R, Group 63, Tempo 3, Group Atoma, Verifica 8+1

Meanwhile, in France, the GRAV – Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel was formed by international artists such as Le Parc, Morellet, Yvaral and others, under the influence of Vasarely.

Italy as a workshop of modernity

According to historian Giovanni Granzotto, if Paris was the headquarters of Kinetic Art, Italy was its true creative workshop. Italian artists were hungry for technology, design and new languages capable of combining dreams, science and utopia.

Kinetic Art thus became a fertile field for exploring the limits of the human eye and the potential of the mind. Each work was an invitation to participate, a real-time experiment between artist, viewer and space.

Antonio Barrese e una delle sue opere di arte cinetica

L’Arte Cinetica ha anticipato molte delle tendenze contemporanee: dall’arte immersiva alle installazioni interattive, fino al dialogo tra arte e intelligenza artificiale.

A distanza di decenni, continua a essere un punto di riferimento per chi cerca una forma d’arte che non si limiti alla rappresentazione, ma coinvolga i sensi, l’intelligenza e l’immaginazione.

Non è un caso che oggi le sue opere siano protagoniste di mostre internazionali, musei e collezioni, riscoperti da nuove generazioni di artisti e curatori. Perché il movimento, dopotutto, non si è mai fermato davvero.

Follow me on:

About me

In this blog, I don't explain the history of art — I tell the stories that art itself tells.