In the works of Giorgio Vazza, between land art and shared memory – ARTIST STUDIES

With Studi d’Artista, this time we move to the mountains, between the waters of Lake Santa Croce and the trails of the Farra d’Alpago Nature Reserve, to meet Giorgio Vazza, a multifaceted artist who intertwines nature, memory, and community. His art stems from a deep pain, that of the Vajont tragedy, and is transformed into installations made of wood, earth, and silence.

An intense, human, moving journey.

ARTIST STUDIOS

A journey through Italy to discover contemporary artists

curated by Laura Cappellazzo

I met Giorgio Vazza on 19 July, during the inauguration of his latest installation, created as part of a fifteen-year project by the Municipality of Alpago (BL) for a summer workshop on Land Art with the Gruppo Operativo Giovani (Youth Action Group). The installations of intertwined branches greet visitors to the central path of the Lake Santa Croce Nature Reserve in Farra D’Alpago, which leads to the lake.

It was a splendid morning: the group of young people presented this year’s programme, the institutional figures expressed their pride in a project that brings beauty to the area and manages to involve young adolescents, and the artist Vazza was visibly moved.

What struck me most, immediately after the beauty of the works installed in a wonderful natural setting, was the strong sense of community that had developed around this artistic project and the figure of Vazza. It was like touching the power of art with my own hands, which, in addition to being an aesthetic message of universal significance, can also weave relationships and raise awareness of the need to care for the local area.

Giorgio Vazza, as well as being a highly regarded and recognised artist, is also a very kind and approachable person, and he generously gave us an interview.

IN GIORGIO VAZZA’S STUDIO

Good morning, Vazza. Thank you for your time and for agreeing to introduce yourself to our readers. Let’s start with the introductions: who is Giorgio Vazza?

I am an artist… because art has always been a part of me since I was a child, in a very intimate way, like a personal necessity. And in fact, to tell you about myself, I have to start with a very personal experience: I now live in Sitran d’Alpago, but I was born in Longarone, in the hamlet of Muda Maè. I was 11 years old when the dam tragedy happened… I won’t tell you what I saw… it was utter desolation. Our family was saved from the flood, but we lost all our loved ones: friends, relatives… there were 35 bodies just below my house. My grandfather came to get me: I remember walking through the rubble, with dead bodies everywhere; my mother held me in her arms and told me not to look.

This was something powerful that happened to me, a torment that has accompanied me throughout my life, but which I have never been able to talk about. In 2013, a friend gave me a 100-metre roll of paper: I started drawing what I remembered, quick strokes, it was like breathing. I was sweating as I drew… it was a very powerful experience, transformed into a series of pencil drawings, barely sketched figures with empty faces and subtle landscapes. In 2018, I transferred those sketches into small boxes, I made seven of them, like a black box from an aeroplane. It was a moment of emptying, but a necessary one. Here too, in the Land Art of the Oasis, I dedicated a work to Vajont: it is entitled “V as in Veste (clothing) – V as in Vuoto (emptiness) – V as in Vajont” and is reminiscent of shrouds. You see, behind each of my works there is a thought, something very profound that I want to express.

And where did you learn to do this, to be able to convey these thoughts of yours?

I am self-taught. In Castellavazzo, the village where I lived, Sirio Sanibeni, an artist from Florence, came every summer, and I would sit next to him and watch. That’s how I started painting. I also spent time with Domenico Bettio, an artist from Ospitale di Cadore, and for many years, as a boy, I went to the Arte Centro in Longarone every Friday, where I was able to learn more about technique and meet other artists.

You use many different art forms: painting, drawing, book objects, Land Art installations. You have recently started collaborating with Musinf (Museum of Modern Art, Information and Photography) in Senigallia on some marble works… but what was your first artistic love?

Painting, definitely. I remember when I was little, there was an ancient Roman bridge in Muda Maè. One day, I was dazzled by a painter who came up to my mountains with his easel and started painting the landscape. The movements he made, the magic with which the panorama was transferred from view to canvas, the technique of colour to give perspective… I remember being fascinated.

In those years, children like me were sent to summer camp by the sea. I didn’t like leaving, I hated that suitcase… leaving my family, I felt homesick. But I drew the sea, the boats… and that gave me some comfort.

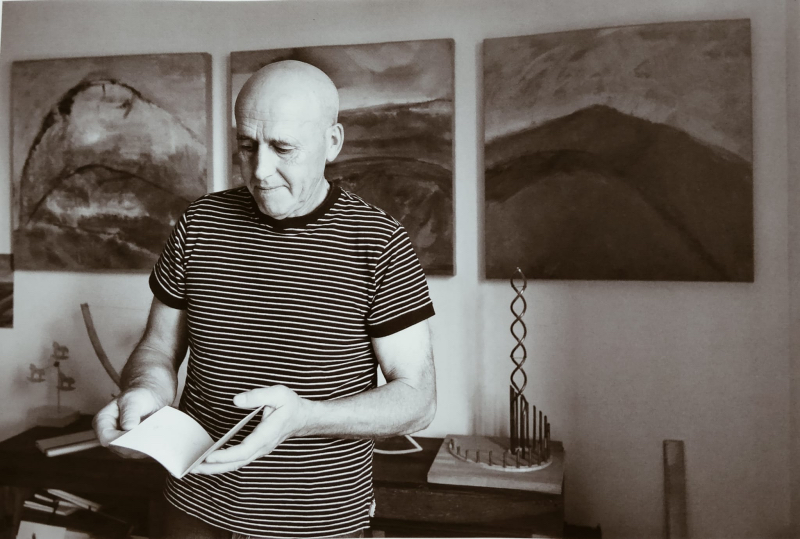

Giorgio Vazza

Our column is called ‘Artist’s Studios’: may I ask you what your studio is like?

(Smiles, ed.). My studio? I have more than one! Because I had taken over the house and my wife sent me to the barn next door, a few hundred metres from the house, where there was still a hayloft upstairs. That’s where I do most of my painting, partly because of the smell of paint, turpentine, thinners… if I’m at home, everything gets impregnated with that smell. In the barn, which I’ve adapted over time, I’m free to create and use the materials I need without disturbing anyone.

Your painting is sparse: it is based on colours, wide spaces, panoramas of your mountains and instils peace. In fact, someone has described your painting as “gentle, airy, almost intangible”. Would you like to talk about it?

For me, drawing is like breathing, it is immediate and I don’t have much on my mind. I try to do my best, but above all it is immediate.

With painting, on the other hand, I look for relationships and balances between colours; it’s something more thought out. And I like working on the square, so it’s also something mediated by physical space. The mountains give me peace, serenity and a subject that I often paint. To create the “Pascoli vaganti” (Wandering Pastures) cycle, I followed my nephew, who has a flock and is a shepherd, for two years. He is a loner like me. It was wonderful to follow him; I realised that the work of a shepherd is like the work of an artist: it is just you and what you have to do. Like me when I draw, like him with his sheep, like her when she writes; we are alone when faced with the decisions we have to make: which line should I use? Which pasture should I choose to stop at? Which word should I use? For me, it was a really powerful experience, being in contact with the mountains, which are beautiful, but also tiring, sometimes even cruel.

Instead, your Land installations are very physical, made of wood, stones, branches… Can you explain what Land Art is and why you chose it as a workshop with teenagers?

Years ago, I did a painting workshop in schools, but it was a difficult experience because group work is complicated. And then sometimes the kids had very bad situations at home, which they then conveyed through very powerful drawings, which I resonated with, and I decided not to continue. In 2017, I was asked again to do an art workshop with young people, but I thought I’d do Land Art… so at least if something broke, it wouldn’t be a big deal! The nest was our first installation, and they themselves experienced it as a cradle of life, as a message to take care of the space in which they lived. That’s exactly what I want to convey with my installations: to encourage meditation, thought, to get away from crowded places and go deep within ourselves.

I wasn’t lucky enough to have adults who planted ideas and thoughts in me. I really hope to do that with them. And then look, (points to the people around us, ed.) there are grandparents, parents bringing snacks… a community has been created. Also because you don’t know how much these kids eat! I get on well with them. There are adults who supervise them while we work. They learn to respect time, to carry out tasks, to recognise trees and wood. They feel that they are capable of creating something beautiful.

Can you tell us about the process of creating a work like this?

I choose the subject according to the message I want to convey: this year it was the boat, a symbol of going deep, of not staying on the surface. In my studio, I sketch and imagine the measurements. Then, in the physical location, I stake out the area: if I have a 7.5-metre boat in mind, for example, I have to think about the poles that will support it from the ground, tied with wire. I use acacia poles, which are durable. With hazel branches taken from the woods here, I make the curves and then tie them with wire. Meanwhile, I pay close attention to harmony, the harmony of the work, the golden ratio… which I taught the children to measure with their bank cards… First, we make the skeleton and the supporting structure, and then we fill the work with hazel and larch.

Two of his statements struck me deeply: ‘Land art works belong to everyone; you can’t buy them and take them home, but they belong to the territory in which they are located.’ And again: ‘When a land art work is destroyed by bad weather, that’s okay, it’s part of the process because what we took from nature to create the work has returned to nature.’

I ask her if she can elaborate on these dynamics between installation and territory, between man and nature and art…

When you create a work of land art, you borrow material from nature. Then, once you have made it, it is no longer yours: it belongs to the territory, which changes and shapes it. It is a continuous change that mutates and evolves; it is ephemeral art that changes with the colours of the seasons and the weather… If you walk in those places, you are fascinated by these works, and you are led to meditate, to create thoughts.

So is this the meaning of making art for you?

For me, art is something that makes me feel good. If you think about it, we live in dramatic times. Art must communicate something to us who live in these times. Art is the thermometer of society, it tells us who we are. Politics is blind, but art sees very well and tries to convey messages that make us reflect: on life, on time, on nature…

Post edited by: Laura Cappellazzo

Follow me on:

About me

In this blog, I don't explain the history of art — I tell the stories that art itself tells.