WORKS AND TICKETS MUSÉE MARMOTTAN MONET

What are the works and how to book tickets for the Musée Marmottan Monet?

Here is a post to discover some of the most significant works of the master of Impressionism kept in the museum, which is the repository of the largest collection of works by Claude Monet in the world.

The museum’s main objective is to disseminate knowledge of Monet’s work on an international level and is a unique place to visit.

Works and tickets Musée Marmottan Monet

Musée Marmottan Monet

In 1932, Paul Marmottan (1856-1932) bequeathed his collections and his hôtel particulier, located in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, to the Académie des beaux-arts, which turned it into a museum in 1934.

The neoclassical furniture and paintings make up the first collection of the Parisian institution and illustrate Marmottan’s passion for the art of the First Empire. An academic art opposed to that of the Impressionists, who were interested in transcribing sensations in paint with rapid, sketchy touches.

Yet an anecdote brings the two aesthetic visions together.

To crush the first exhibition of Monet and his friends in Nadar’s studio in 1874, the journalist Louis Leroy, in an article published in the satirical newspaper Le Charivari, wrote about a pupil of Bertin’s who was on the point of choking at the sight of paintings by Pissarro or Degas, and who received the coup de grace in front of Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise” (1872), the work that gave Impressionism its name.

In the end, however, it was Bertin, and not Monet, who disappeared into thin air.

A century later, history would unite the Neoclassical painters and the Impressionists in the same box, making the Musée Marmottan Monet the repository of the world’s first collection of Monet’s works following the bequest of the painter’s youngest son and direct descendant, Michel Monet. More than a hundred works have been added to the institution’s collections and the museum has added the name of the master from Giverny to its own.

TICKETS MUSÉE MARMOTTAN MONET

The Musée Marmottan Monet is the best museum for those who want to get a closer look at masterpieces by Monet and other Impressionists such as Gauguin, Degas and Morisot.

More than 100 of the master’s works are kept here, coming from the collections of friends and relatives over many years, including his most famous works such as Impression, Sunrise and Water Lilies.

The museum is very popular and booking is strongly recommended to avoid long queues at the entrance and possibly not getting in.

Choose a date from the calendar to visit the museum (closed on Mondays).

If you would like to visit the Musée Marmottan Monet with a guide who can select the most important works and answer all your questions about the museum and Monet, I recommend booking a guided tour.

A tour for small groups is available, giving you the opportunity to discover details and anecdotes about Monet’s work and life..

MUSÉE MARMOTTAN MONET WORKS TO SEE

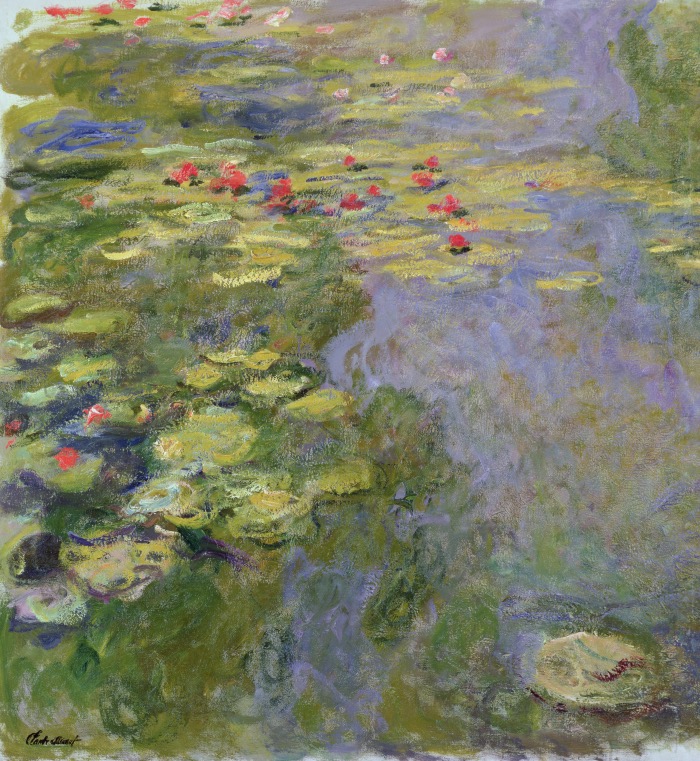

Water Lilies (c. 1916-1919)

Claude Monet spent his whole life immersed in the landscape.

In 1883 he moved to Giverny where he spent the rest of his life and his garden, which he recreated from scratch, was the final source of inspiration for his work.

Monet devoted many hours to depicting all the facets of the plant world around him and produced a large number of paintings, painting from life in the case of small works, or in the studio for larger works.

As time went by, he made the water lily pond the sole subject of his canvases, eliminating the edges of the pond from his compositions in favour of a single detail: the water, the mirrored reflections, the water lilies, until he produced his Grandes Décorations.

Claude Monet (1840-1926) Ninfee, 1916-1919 circa Olio su tela, 130×152 cm

Parigi, Musée Marmottan Monet, lascito Michel Monet, 1966. Inv. 5098

© Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Images

The Argenteuil railway bridge (1874)

In the nineteenth century, the development of the railway network and the invention of colour in tubes enabled painters to travel and paint in the open air.

However, this new opportunity came with certain limitations. The artist had to take his equipment with him, so he preferred small canvases, which were easier to transport. In addition, he has to paint quickly in order to catch what he sees.

That is why his brushstrokes were quicker and the range of colours he used, working in broad daylight, lighter.

Monet was introduced to this practice by Johan Barthold Jongkind (1819-1891) and Eugène Boudin (1824-1898), who travelled extensively throughout France and abroad to paint landscapes and seascapes, amongst other things.

During his plein air painting sessions, he sometimes had an assistant assist him.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Il ponte ferroviario di Argenteuil, 1874 Olio su tela, 14×23 cm. Parigi, Musée Marmottan Monet, lascito Michel Monet, 1966. Inv. 5037

© Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images

Crag and Porte d’Amont. Morning effect (1885)

By choosing to leave their studios to paint from life, the Impressionists broke the hierarchy of painting genres.

For them, the sensation produced by a landscape or scenes of modern life was more important than the subject itself.

Monet, a master of plein air painting, spent his whole life trying to capture the luminous variations and chromatic impressions of the places he observed. More than the subject, he was interested in the way it was transfigured by the light.

In order to capture the ever-changing luminosity, the painter works quickly, with brushstrokes that follow one another rapidly, and he does not hesitate to visit sites where violent climatic changes occur.

The Normandy coast with its magnificent sunsets, or the Creuse region, discovered during a stay in 1889, offered him the opportunity to portray the intensity of light in a natural environment that was still wild.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Falesia e porta d’Amont. Effetto del mattino 1885. Olio su tela, 50×61 cm. Parigi, Musée Marmottan Monet,

lascito Michel Monet, 1966. Inv. 5010. © Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images

Charing Cross Bridge (1899-1901)

London was a laboratory for experimentation in Monet’s career.

The ghostly landscapes created by factory fumes and the mist on the Thames enabled him to work, as he himself said, on what was impossible in painting: the impalpable mist covering the architecture and the changing light that skims the surface of the water.

The views of Charing Cross Bridge and the Houses of Parliament, painted during several successive stays, opened up a new phase of research for him, which was fully manifested when he returned to Giverny.

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Il ponte di Charing Cross, 1899-1901 circa Olio su tela, 60×100 cm. Parigi, Musée Marmottan Monet, lascito Michel Monet, 1966. Inv. 5101 © Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images

Water Lily Pond (c. 1917-1919)

From 1914 until his death in 1926, Monet produced 125 large panels depicting the water garden at Giverny.

A selection of these works, now known as the Water Lilies of the Orangery, the painter offered to the French State.

These monumental paintings, produced directly in his studio, take the research already begun with the Water Lilies of 1903 and 1907 to the extreme.

By depicting a small part of his pond in such a large format, Monet not only cancels any real reference to perspective, but suggests immersing the viewer in an expanse of water that becomes a mirror: the clouds and the willow branches are reflected in the surface of the pond, and the top and bottom are now indistinguishable.

These landscapes without beginning or end invite a contemplative experience in which the representation of a flower or a detail of nature is enough to suggest its immensity.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Lo stagno delle ninfee, 1917-1919 circa. Olio su tela, 130×120 cm. Parigi, Musée Marmottan Monet,

lascito Michel Monet, 1966. Inv. 5165 © Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images

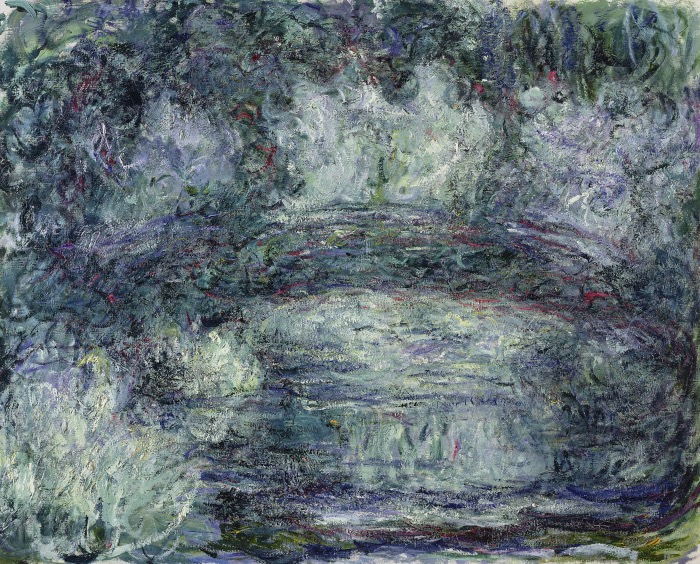

The Japanese Bridge (c. 1918-1924)

In 1908, Monet fell ill with cataracts, a disease which prevented him from seeing clearly and affected his perception of colours. As the painter struggled with this progressive blindness, his palette shrank and, as we see in the Japanese Bridge cycle, was dominated by shades of brown, red and yellow.

His painting became more gestural: the hand holding the brush became visible on the canvas. Form fades away, giving way to movement and colour, and from representation he turns to sketching, which becomes increasingly indecipherable.

These easel paintings, unparalleled in Monet’s artistic career, were to have a profound influence on the abstract painters of the second half of the 20th century.

Claude Monet (1840-1926), Il ponte giapponese, 1918-1924 circa Olio su tela, 89×100 cm. Parigi, Musée Marmottan Monet, lascito Michel Monet, 1966. Inv. 5094 © Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images

The Roses (c. 1925-1926)

Flowers accompanied Monet throughout his life, in both his private and professional life.

The garden at Giverny, with plants blooming in every season, is Monet’s homage to the changing colours and ephemeral nature of flowers, and The Roses, painted in 1926 at the age of 85 (the same year he died), is the last celebration of this.

The unfinished nature of the painting enhances the impression of fragility of the roses, whose light buds delicately stand out against a blue sky.

The composition depicts a few branches of the rose garden and recalls the Japanese prints that the painter collected with such passion.

With The Roses, Monet pays tribute to the nature he portrayed so well, along with the fragility and transience of his surroundings.

Claude Monet (1840-1926) Le rose, 1925-1926 circa Olio su tela, 130×200 cm. Parigi, Musée Marmottan Monet, lascito Michel Monet, 1966. Inv. 5096. © Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris / Bridgeman Images