GRIBOUILLAGE: WHEN DOODLING BECOMES ART

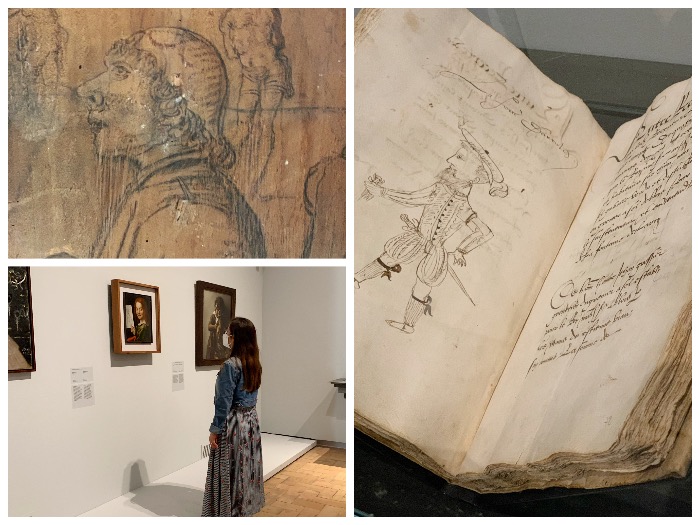

I had the opportunity to visit an exhibition that, with unusual juxtapositions, sheds light on lesser-known aspects of the practice of drawing.

Gribouillage/Scarabocchio. From Leonardo da Vinci to Cy Twombly is the exhibition curated by Francesca Alberti and Diane Bodart that takes place first in Rome, at the Academy of France – Villa Medici, then in Paris, at the Beaux-Arts.

The exhibition project explores the hidden side of art making and invites visitors to move their gaze to the back of paintings, the walls of workshops, the margins of a book or the walls of cities.

Two complementary exhibitions to address the many facets of doodling in art.

In this post I propose the sections of the Rome exhibition, which has the merit of underlining how experimentation and the search for a primordial sign, which does not respect any academic rule, is a necessity present not only in the contemporary era.

Gribouillage: when doodling becomes art

Gribouillage: when doodling becomes art

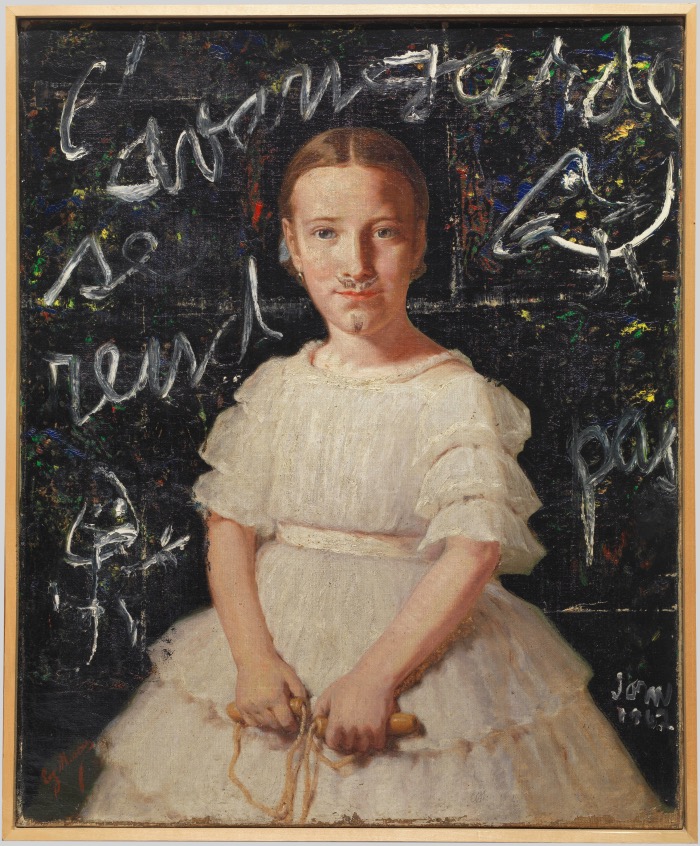

Jorn Asger (dit), Jorgensen Asger Oluf (1914-1973). Paris, Centre Pompidou – Musèe national d’art moderne – Centre de crèation industrielle. AM 2016-700.

In recent decades, various sketches, doodles and caricatures have been found in the margins of works by great artists, prompting scholars to consider art from a new angle.

This hidden side of artistic production, in fact, reveals some original aspects of an artist’s life, the work within a Renaissance workshop and brings out those little-known aspects that lead to the birth of a masterpiece.

Indeed, artists of all ages have an almost instinctive relationship with drawing, and Gribouillage/Scarabocchio proposes a dialogue between Renaissance graphic production and contemporary works, highlighting the multiple aspects of the doodle phenomenon.

IN THE SHADOW OF THE WORKSHOP

On the backs of the plates and canvases of the most famous Renaissance masters, on the walls of their workshops or underneath detached frescoes, in the margins and on the reverse side of their drawings or the copper matrices of their engravings, a wealth of clumsy sketches and extraordinary graphic games are hidden: schematic profiles and grotesque heads, disproportionate or ridiculous figures, autonomous ornamental lines and trials of hatching with abstract shapes.

These hidden drawings, probably made in a moment of pause, are traces of the daily life and collective work of the workshop, of which only fragments are known.

The presence of these scribbles reveals the presence of experimental graphic gestures, which underlie the creation of the great works we admire today in museums, churches and places of culture.

A practice long ignored by historians and critics because it is outside the rules of drawing and cannot be assimilated to a reference code or precise genre.

THE GAME OF DRAWING

Scribbles in the margins of a book or on the back of a painting represent the place of freedom but also of chaos, the suspension of concentration but also play.

It is precisely in this unregulated space that writing professionals such as accountants, notaries, clerks, scribes and copyists give free rein to the pleasure of boredom in their moments of rest and fill their manuscripts with scribbles, letters and figures without order or measure,

Artists too take possession of this space of freedom and play with drawing, creating figures and doodles at will, reducing forms to simple outlines, synthesising ideas with a few strokes.

The margins of a work and occasional surfaces are filled with heads, outlines and superimpositions made in haste and over thought.

These experiments are a game, but they allow us to observe the creative process and make us reflect on the fact that, at a certain point, caricature went from being pure entertainment to becoming an art form in its own right.

INCULTORY COMPOSITIONS

Incult composition: an oxymoron conceived byLeonardo da Vinci and referring to quick, rough sketches used to identify the figure to be represented and its movements.

This procedure of Leonardo’s was used to find a form without defining it, but it has opened the way to numerous experiments by artists, especially since the 20th century, who seek that state, between consciousness and unconsciousness, to transform the hand into an instrument capable of revealing thought and what is concealed within the mind.

The sheets of inculturated compositions are filled with digressions and erasures, until they become illegible, like stains generating ‘potential images’ that Leonardo invited us to observe, on dirty walls full of cracks, to nourish the imagination needed to compose stories.

Agostino Carracci, serie di caricature (1945 ca)

CHILDHOOD IN ART

With his ‘Ritratto di fanciullo con disegno‘ (Portrait of a Child with Drawing), Giovanni Francesco Caroto inaugurates a season of paintings that play with children’s drawings within the pictorial composition.

In these perfectly accomplished paintings, the rudimentary depictions of childhood introduce a reflection on the birth of art and the desire to make art.

Around the image of the child scribbling books and notebooks, or daubing the walls with drawings, the myth of the artist who reveals his aptitude for art from an early age is formed.

It was the avant-garde artists such as Vassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter who, in search of the vital and joyful trait of the child’s doodle, began to collect children’s drawings which they then exhibited alongside their works.

Paul Klee, on the other hand, included childhood drawings in his courses at the Bauhaus and cited them as models for inspiration.

THE LURE OF THE WALL

The wall is a surface that has always attracted artists and children.

To draw on a wall is to leave a sign of one’s passage and to entrust that wall with the task of spreading a message.

Between juxtapositions and superimpositions, the signs of these graphic actions are consigned to the walls in which ancient and primordial signs coexist and are re-enacted by those who come after.

These juxtapositions of signs from various eras, produced by the all-too-human need to leave a mark, fascinate artists who claim the authenticity of art made in the street.

Graffiti, often associated with the urban periphery and the marginalised, became the source for a renewal of art in the 20th century.

The drawing, the mark and the doodle on the walls of metropolises, but also on the walls of a prison or on the skin of men, where those marks are called tattoos, are a gesture of vital subversion.

Thus the doodle becomes a rebellious gesture and is capable of communicating universal messages, blurring the difference between doodle and work of art.

JACKS AND PUPPETS

During the 20th century, the search for a primitive naivety led the European avant-gardes to identify in children’s drawing the cues to regenerate art with a subversive force that escaped the constraints of academic conventions.

While more traditional art criticism constantly uses infantilism, primitivism and backwardness as arguments to condemn any formal revolution, artists adopt drawing as a new field of experimentation.

If Giacomo Balla identifies in children’s spiral graffiti the origin of Futurism, Dubuffet and the Art Brut group, as well as the members of CoBRA, focus on achieving an expressive autonomy of the line that does not necessarily have to imitate or reproduce reality or be inspired by the masters of the past.

This rediscovered freedom of the sign also passes through alteration and destruction, but also through meditation.

Luigi Pericle, Senza titolo (Matri Dei d.d.d.), 1965. Archivio Luigi Pericle

LUIGI PERICLES

The figure of Luigi Pericle appears in the artistic panorama of the second half of the 20th century. He was a refined and cultured artist, a painter, but also a thinker, a scholar of theosophy and esoteric doctrines, and an illustrator.

The Gribouillage/Sacrabocchio exhibition does not dedicate a special section to this artist, but I believe it is worth pausing in front of the work selected for this exhibition, as it allows us to reflect on drawing as experimentation, research and meditation.

Luigi Pericle, who lived on the slopes of Monte Verità, was a multifaceted personality in the artistic scene of the second half of the 20th century. For him, artistic creation was an integral part of a path of spiritual evolution, and it is his mysticism that is the key to understanding his paintings, the thousands of chine drawings preserved in his archives and the many illustrations he produced for important international magazines.

Pericles devoted himself to drawing constantly and daily, approaching this practice as a form of meditation for himself and for the observer.

The painting on display, in both the Rome and Paris exhibitions, is a tool for penetrating the mysteries of existence.

The figures we observe are essential, they seem to emerge from an ancient past and are imprinted on a surface of insubstantial thickness.

If for Renaissance painters drawing, and even doodling, was thought and representation of an idea, for Louis Pericles it was spiritual research.

EXHIBITION INFORMATION: GRIBOUILLAGE/SCARABOCCHIO

Gribouillage/Scarabocchio. From Leonardo da Vinci to Cy Twombly

From 3 March to 22 May 2022

Villa Medici – Rome

From 19 October 2022 to 15 January 2023

Beaux-Arts – Paris

Exhibition produced and organised by the Academy of France in Rome – Villa Medici and the Beaux-Arts in Paris.

With the support of the Musée national d’art moderne – Centre Pompidou, Paris.

In collaboration with the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica, Rome

THE CATALOGUE

The exhibition catalogue brings together the 300 works exhibited in Rome and Paris and is published in Italian and French by Villa Medici and Beaux-Arts de Paris éditions.

This reference publication on one of the lesser-known aspects of drawing practice offers an extensively documented synthesis of the two exhibitions.

Conceived and introduced by the curators of the exhibition, Francesca Alberti and Diane Bodart, the catalogue includes seven chapters and brings together previously unpublished contributions by seventeen authors: Emmanuelle Brugerolles, Baptiste Brun, Angela Cerasuolo, Hugo Daniel, Vincent Debaene, Dario Gamboni, Anne-Marie Garcia, Tim Ingold, Giorgio Marini, Philippe-Alain Michaud, Anne Montfort-Tanguy, Mauro Mussolin, Gabriella Pace, Maria Stavrinaki, Nicola Suthor, Alice Thomine-Berrada, Barbara Wittmann.

The graphic project is by Mauro Bubbico.